Learning Outcomes

- Understand how events and individuals shaped the early colony

- Understand the role Henry Parkes played in setting up Australia’s Federation

Syllabus Links

THE AUSTRALIAN COLONIES

The role that a significant individual or group played in shaping a colony; for example explorers, farmers, entrepreneurs, artists, writers, humanitarians, religious and political leaders, and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples (ACHHK097).

- use a range of sources to investigate the role of a particular man, woman or group and the contributions each made to the shaping of the colony

AUSTRALIA AS A NATION

Key figures and events that led to Australia’s Federation, including British and American influences on Australia’s system of law and government (ACHHK113)

- sequence key figures and events and explain their significance in the development of Australian democracy, eg Sir Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, Louisa Lawson, Vida Goldstein

Early life and Influences

Henry’s formal education was in his own words, ‘very limited and imperfect’. He briefly attended Stoneleigh parish school and later joined the Birmingham Mechanics’ Institute. As a boy he was obliged to help support his family, so he worked as a road labourer and in a brickpit.

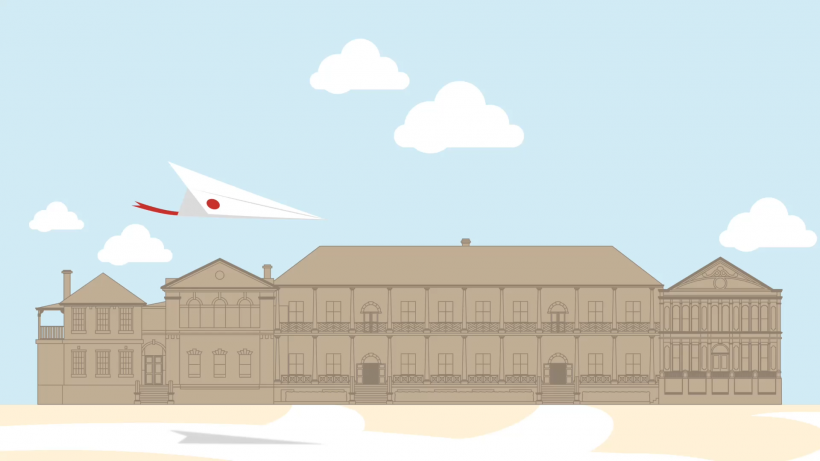

Henry Parkes portrait painted by Julian Ashton in 1913, on permanent display in the NSW Parliament.

YEAR |

HENRY PARKES LIFE EVENT |

| 1815 | Born in England, the youngest of seven children of Thomas Parkes, farmer on Stoneleigh Abbey Estate, and his wife Martha. |

| 1823 | The Parkes family were forced off their farm due to debt in 1823 and the family next moved to Glamorganshire, finally settling in Birmingham in 1825 where Thomas was a gardener and an odd-job man. |

| 1836 | Married Clarinda Varney. |

| 1837 | Parkes began his own business, having previously gained experience as a bone and ivory turner. |

| 1838 | Parke’s business failed and he took Clarinda to London where they survived a few weeks by pawning his tools. They then decided to leave for New South Wales as bounty migrants. |

| 1839 | Parkes and Clarinda sailed from Gravesend on 27 March 1839 in the Strathfieldsaye, their ears ‘incessantly assailed by the coarse expressions and blasphemies’ of other steerage passengers. |

Famous Last Words

Parkes wrote a poem about this decision to leave, ‘A Poet’s Farewell’ where he condemned a society whose injustices meant ‘men like this are compelled to seek the means of existence in a foreign wilderness’.

Before leaving for New South Wales, he told his Birmingham family of his certainty of ‘making my fortune and coming back to fetch all of you’.

Early Struggles in the Colony

Henry Parkes and his wife reached Sydney on 25 July 1839 and Parkes found work as a labourer. By 1840 he worked in the Customs Department, while he slowly saved to buy the tools he needed to set up his own business.

In 1845, he set up as an ivory turner and importer of fancy goods in Hunter Street. By 1850 the business had failed and he was in financial difficulties again. However, Parkes had by this time become deeply involved in literary and political activities, and planned that his business would be used to support his writing.

Finding a New Place in New South Wales

From the 1840s, NSW was growing out of its convict colony status. Parkes and others believed it was time for the colony to start governing themselves and building a new society without the arrival of more ships loaded with convicts.

Parkes’ skills as a writer developed quickly during this period, quite amazing for someone so lacking in formal education. He was briefly Sydney correspondent for the Launceston Examiner, and contributed occasional poems and articles on political and literary topics to the Sydney Morning Herald, the Australasian Chronicle and the Atlas. In 1842 he published his first book of verse, Stolen Moments.

At this time Parkes was one of the colony’s radical patriots. He joined a group of them agitating for the right to vote being extended and land reform. In his first public speech, made at the City Theatre in January 1849, Parkes advocated universal suffrage as the best guarantee that the people would be well represented.

Parkes advocates for universal suffrage in 1849

The people in the United States of America already enjoy it. Why then should Englishmen not have the same privilege? Those opposed to it point to the revolutionary excesses of Paris and Frankfurt a year ago to support their views. They speak of crime and outrage and how the hands of the people had been dyed in blood. But I find the events of last year an argument in favour of universal suffrage. I believe that in those nations it had been too long withheld. If it had been conceded earlier, Louis Phillipe might still be on the throne of France.

Parkes joined the Anti-Transportation League and participated in the great protest which erupted when the convict ship Hashemy arrived in 1849. He also joined the liberal campaigns against what they viewed as the anti-democratic Electoral Act of 1851, which allowed 18 members of the Legislative Council to be appointed.

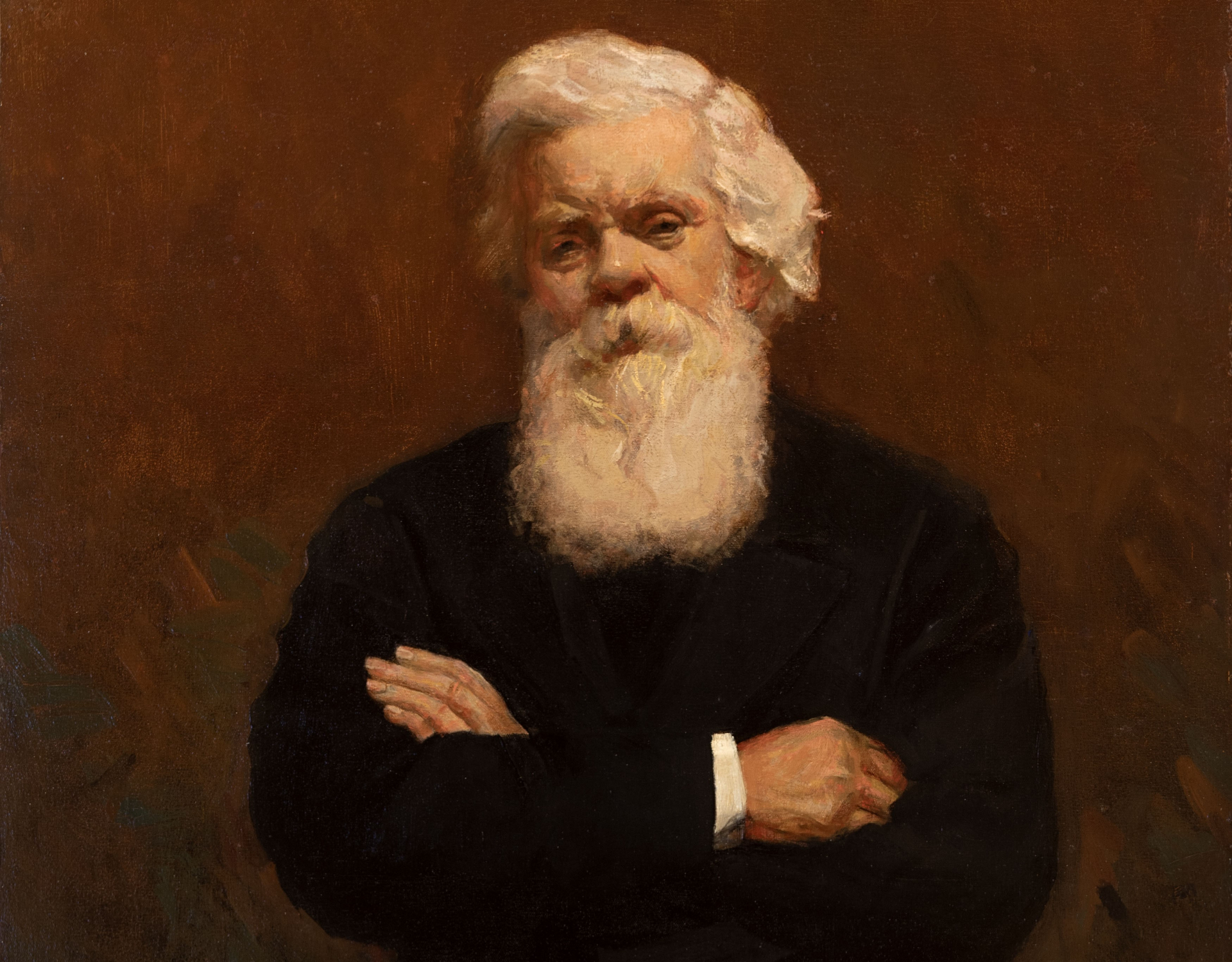

The Empire Office 1872 Pickering, Charles Percy (New South Wales. Government Printing Office) State Library of New South Wales

In 1850, he became the editor-proprietor of The Empire, a newspaper which quickly became the voice of freedom, equality, democracy and human rights in the colony.

Election to Parliament

In 1850 the Australian Colonies Government Act was passed by the British Parliament. It expanded the Legislative Council so that by 1851 there were 54 members, two thirds elected.

The Act also permitted the creation of three other self-governing colonies with a Legislative Council: South Australia, Tasmania, and Victoria.

The Act also permitted the creation of three other self-governing colonies with a Legislative Council: South Australia, Tasmania, and Victoria.

In 1853 a select committee chaired by William Charles Wentworth (pictured) began drafting a constitution for responsible self-government for New South Wales. This would mean NSW would have two houses of Parliament – a lower house with fully elected members to represent the citizens of NSW, and an upper house – a bicameral system of government modelled on the Westminster system.

William Charles Wentworth’s portrait has hung in the Legislative Assembly chamber since 1859 in recognition of his contribution to the development of NSW.

Parkes was committed to opposing William Wentworth’s constitution bill. He decided to seek a place in the Legislative Council to participate more directly in amending the bill. In 1854, he became a member of the Upper House, becoming a member of Parliament for the first time.

The committee’s proposed Constitution Act was placed before the Legislative Council and accepted with some amendments. The revised Constitution Act, with an Upper House whose Members were appointed for life, and the establishment of a fully elected lower house was sent to the British Parliament and, with some further amendments, was passed into law on 16 July 1855 and proclaimed in NSW in November that year.

Responsible Government

Responsible government in NSW was established by the new Constitution. NSW now had two houses of Parliament.

The following year, in March 1856, Henry Parkes won one of four seats in the Sydney city area. Over the next ten years, Parkes would continue to win seats in the Parliament, and then be forced to leave the Parliament again when he experienced serious financial difficulties.

Pictured is the Legislative Assembly in 1871, the chamber in which the new Legislative Assembly including Henry Parkes met. This chamber is still used by the Legislative Assembly today.

Parkes newspaper, The Empire, collapsed in 1858, ending his dream of using the paper as ‘an independent power to vivify, elevate and direct the political life of the country’. He survived bankruptcy proceedings, struggled on with the support of friends and the proceeds of occasional journalism and planned briefly to abandon politics for a legal career. In June 1859 he was back in parliament to represent East Sydney.

Parkes developed a personal following in the House and in 1859-60 emerged as critic and rival of the established liberal leadership. But economic insecurity made him vulnerable, and early in 1861 he accepted an invitation to tour England as government lecturer on emigration at a salary of £1000.In 1863, Parkes returned to Sydney in good spirits, his self-confidence strengthened by the attention he had received from government officials and such literary idols as Thomas Carlyle. In January 1864, Parkes returned to Parliament at a by-election for Kiama, a seat he held until 1870.

The Colony’s First Assassination Attempt

Henry Parkes was involved in an infamous incident that shocked and shamed the colony in 1868.

For the first time ever a member of the royal family, Queen Victoria’s son, Prince Alfred visited the NSW colony, and thousands came out to show their loyalty to the monarch. At a fund-raising event in Clontarf on 12 March, an Irishman named Henry James O’Farrell fired his pistol at close range, hitting the Prince in the back. The bullet missed his spine and lodged in his abdomen – he was transported to the Governor’s residence where a makeshift operating theatre was hastily assembled, and surgeons deftly removed the bullet with a specially-made surgical probe.

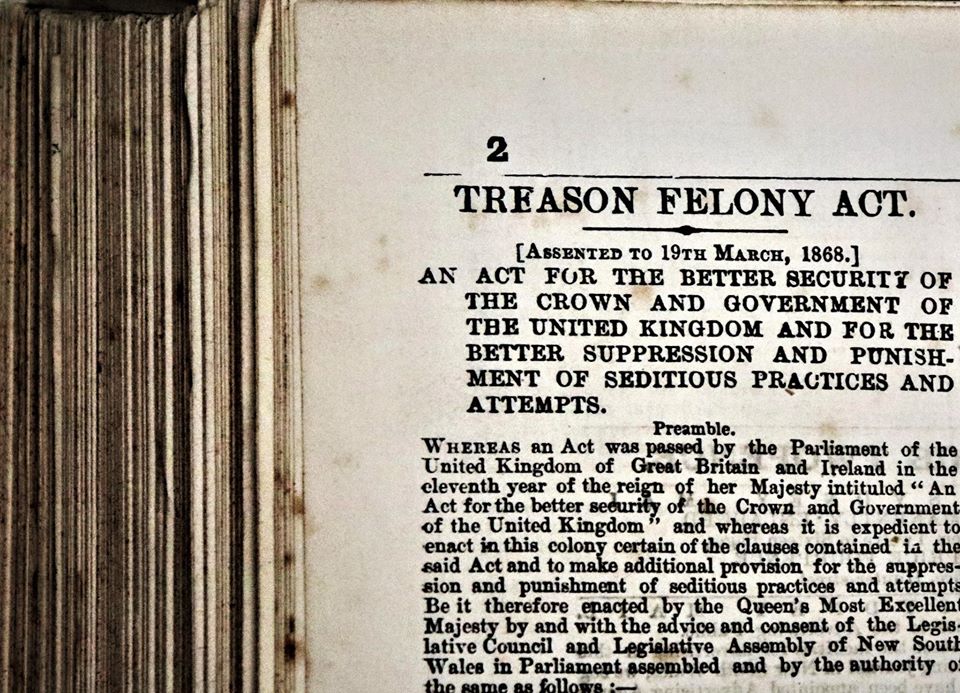

Much relief was felt at the Prince’s full recovery, as well as indignation that this event had brought so much shame to the colony. Henry Parkes in his role as the colonial secretary wasted no time in having O’Farrell arrested, personally interviewing him in Darlinghurst gaol, and ensuring that the Treason Felony Act was quickly passed in the Parliament. O’Farrell was sentenced to death and hanged on 21 April, 1868. No conspiracy was ever uncovered.

Premier Parkes

Henry Parkes served five terms as NSW

Premier between 1872 and 1891. Not only is this the most terms served by any

Premier; if added together Parkes is the longest serving NSW

Premier.

Parkes was responsible for important reform including:

- establishing the hulk Vernon as a nautical school for destitute boys

- the Act requiring the inspection of hospitals

- bringing to Sydney under Lucy Osburn, nursing sisters trained by Florence Nightingale.

- In 1866 the Public Schools Act passed the Legislative Assembly. This measure was Parkes’s first important contribution to education reform. The national and denominational systems of education at the time came at a high cost to the government, so this education reform rationalised expenditure by placing both systems under a Council of Education which would also oversee teacher training and the content of secular lessons.

Parkes remained dedicated to the monarch, Queen Victoria and acknowledged her golden jubilee on 20 June 1887 by reading one of his own poems in the Legislative Assembly Chamber. However, he continued to develop a strong belief in Australia being its own country, as well as maintaining its links to the Commonwealth. This satisfaction at Australians being the chief actors in all that is important to Australia was a prominent feature in Henry Parkes’ life. At the election of Sir J. P. Abbott to the office of Speaker of the Legislative Assembly, he expressed his admiration that the new Speaker was a native-born Australian.

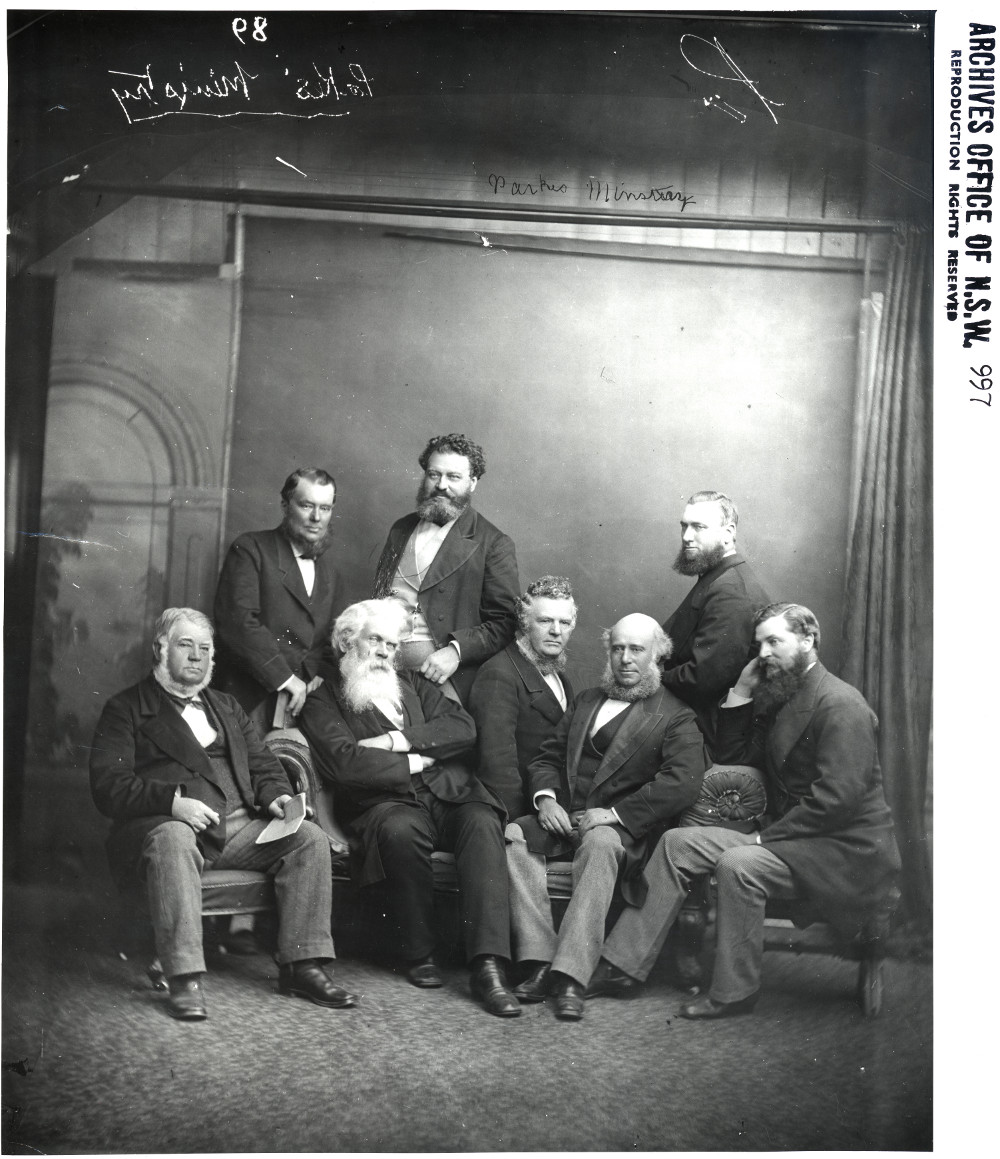

Image NSW State archives Title: Sir Henry Parkes and members of his Ministry Dated: No date Digital ID: 4481_a026_000784 Rights:

“The time is coming, when we must all be Australians, and it is a gratifying circumstance to see the men born in the country aspiring to, and fitly qualified for, the highest offices in the State.”

The Move to Federation

The Australian colonies had developed separately for the first hundred years of their existence but by the 1880s a move towards economic and social integration had started. The tariffs levied on goods moving across borders began to be seen as burdensome and a sense of Australian nationalism was growing.

Perhaps the greatest stumbling block in the way of federation was the ideological division between the two most populous colonies. Victoria was committed to trade protectionism and advocated protective tariffs, believing they would allow industry to grow and provide employment. By contrast, New South Wales steadfastly supported free trade.

The demographics of the colonies were also changing. By 1888, 70 per cent of Australia’s inhabitants were born here. Across the British Empire there was growing enthusiasm for federation within self-governing colonies. Defence of its colonies was becoming an economic and diplomatic issue for Britain. Between July and October 1889, General Sir James Bevan Edwards toured Australia and reported on its defences. He noted that the colonial military lacked organisation, training and equipment and that, ‘forces should at once be placed on a proper footing; but this is, however, quite impossible without a federation of the forces of the different colonies’.

On 15 June 1889 Parkes had a long conversation with New South Wales Governor Lord Carrington who was an advocate of federation. During the discussion Parkes boasted he could federate the colonies in 12 months and Carrington, pandering to the politician’s well-known vanity, dared him to do so. Parkes decided to put all his efforts into the movement. On 15 October 1889 he telegraphed the premiers of the other colonies suggesting a conference to discuss a new constitution and soon after travelled to Brisbane to consider the situation with his Queensland colleagues.

Tenterfield Oration

In October 1889, on his return from Brisbane, Parkes stopped in Tenterfield, northern New South Wales. Tenterfield had a special place in Parkes’s life because in the colonial election of 1882 he had lost his East Sydney seat and the next day was allowed to run in the Tenterfield seat where the local population returned him to parliament.

For Tenterfield, the unfederated nature of the colonies was of particular concern. Its position close to the Queensland border meant that much of its trade was inhibited by high tariffs. Discussions around colonial defence also affected Tenterfield because it was rural towns that contributed the men and equipment to the new light horse military units the colony was raising.

In the Oration, Parkes argued that federation would enable the military in each colony to unite as a single national army under the command of a single national government. He also argued that it would enable Australia’s railway gauges to be of a uniform width. The Tenterfield Oration is significant because it is seen as the first direct appeal to the public rather than to a political audience for federation.

Parkes spent the night in Tenterfield and the speech was reported in the Sydney newspapers the next day. Lord Carrington telegraphed him to immediately return to Sydney to deliver the same speech there as soon as possible. Parkes did so and then presented similar addresses 15 times in different locations over the next nine months.

Constitutional Conventions

As a first step towards federation, Parkes recommended that a convention be held comprising delegates from each of the colonies to draw up a constitution. The first of the Constitutional Conventions was held in Melbourne in 1890, and the delegates then met in different colonial cities over the next decade to draft the constitution. Read more about them on our dedicated page Federation and the Constitutional Conventions.

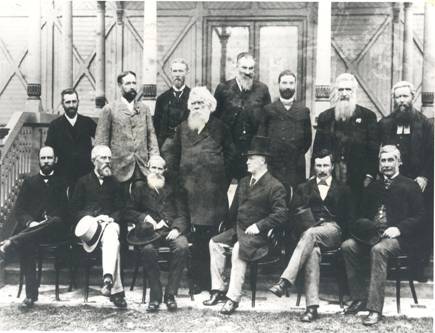

Parkes pictured in the centre. Delegates to the Australasian Federation Conference, Melbourne, 1890, National Library of Australia

The Australian Constitution was contained in the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Bill, which was endorsed by the voters of each Australian colony at referendums in 1898, 1899 and 1900, passed by the British Parliament, and given Royal Assent on 9 July 1900.

Henry Parkes died in 1896, five years before the process he initiated to federate the colonies into one nation was completed. Australia became a federated nation on 1 January 1901.