Learning Outcomes

- Identify aspects of the British and USA systems of government that form part of Australia’s system.

- Identify events leading to the establishment of democratic principles in Australia’s system of government.

- Understand the role the constitutional conventions played in Australia becoming a federation.

Syllabus Links

AUSTRALIA AS A NATION

Key figures and events that led to Australia’s Federation, including British and American influences on Australia’s system of law and government (ACHHK113)

- identify the influences of Britain and the USA on Australian democracy

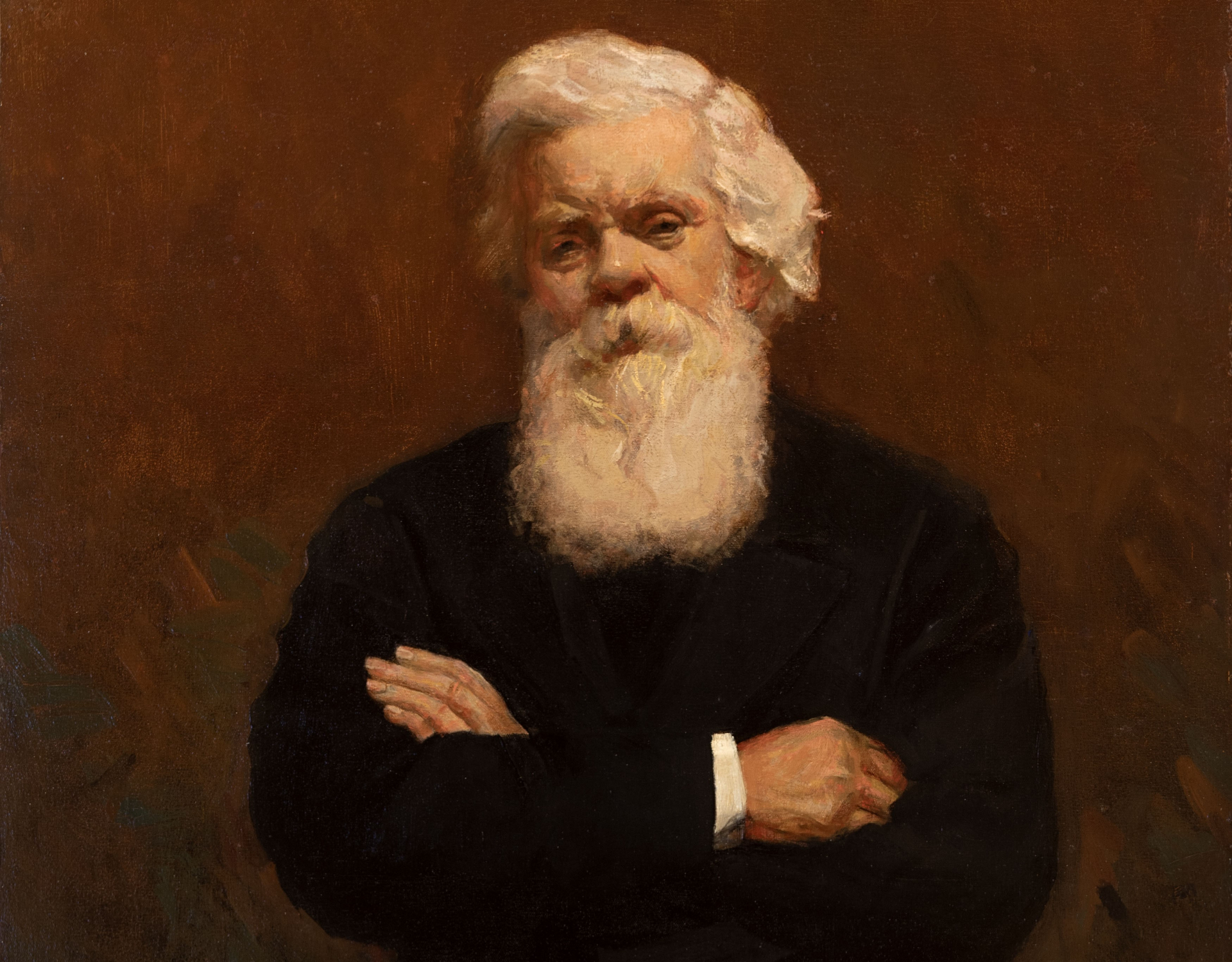

- sequence key figures and events and explain their significance in the development of Australian democracy, eg Sir Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, Louisa Lawson, Vida Goldstein

The First Constitutional Convention

The Journey to Federation

To understand how democracy developed in early NSW colony prior to the Constitutional Conventions visit our Development of Democracy Timeline.

The Australian colonies developed separately for the first hundred years but by the 1880s a move towards economic and social integration started. The tariffs levied on goods moving across borders began to be seen as burdensome and a sense of Australian nationalism was growing.

Perhaps the greatest stumbling block to federation was the differences between the two most populous colonies in terms of their approaches to trade. Victoria was committed to trade protectionism and advocated protective tariffs, believing they would allow industry to grow and provide employment. On the other side, New South Wales steadfastly supported free trade.

Did You Know?

By 1888, 70 percent of people in Australia were born here. Across the British Empire there was growing enthusiasm for federation within self-governing colonies like Australia. Defence of its colonies was becoming an economic and diplomatic issue for Britain. Between July and October 1889, General Sir James Bevan Edwards toured Australia and reported on its defences. He noted that the colonial military lacked organisation, training and equipment and that, ‘forces should at once be placed on a proper footing; but this is, however, quite impossible without a federation of the forces of the different colonies’.

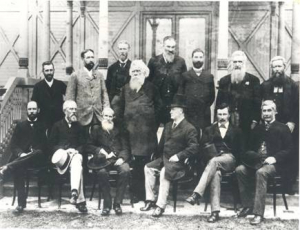

On 15 June 1889 Henry Parkes had a long conversation with New South Wales Governor Lord Carrington who was an advocate of federation. During the discussion Parkes boasted he could federate the colonies in 12 months and Lord Carrington, pandering to Henry Parke’s well-known vanity, dared him to do so. Parkes decided to put all his efforts into the movement. On 15 October 1889 he telegraphed the premiers of the other colonies suggesting a conference to discuss a new constitution and soon after he travelled to Brisbane to consider the situation with his Queensland colleagues. He then delivered an address to the people of Tenterfield on 24 October 1889 where he called for an Australian conference to consider a federation. It was reported in the Sydney Morning Herald the next day, and so began a series of addresses across the colony to engage the people with the idea of an Australian federation.

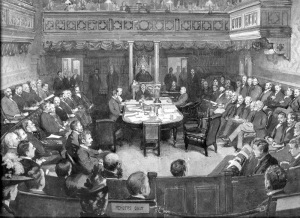

Delegates to the Australasian Federation Conference, Melbourne, 1890, National Library of Australia

The first Australasian Federation Conference of colonial leaders seeking federation was held in Melbourne from 6 to 14 February 1890. Leading politicians from the six Australian colonies and New Zealand affirmed the desirability of ‘an early union under the crown’ and committed themselves to persuading their governments to send delegates to a convention which would ‘consider and report’ on a scheme for a federal constitution. However there was not complete agreement on when the colonies would federate and what changes such a union would mean for each of the colonies. Concerns over tariffs charged on trade between the colonies was a source of disagreement between the colonies, amid concerns on how each colony would continue to raise revenue.

Debate also turned to the British, Canadian and American constitutions and what lessons could be learnt to inform the formation of the Australian federation.

Dr. Cockburn - delegate from South Australia

“…we should have considerable difficulty in following the example of America, because the whole Constitution of the United States of America is so far removed from anything which has ever obtained under British rule. In America there is no such thing as responsibility of Ministers to Parliament, and in this respect, I am sure, no member of this Conference would suggest that we should follow the example of the United States.

The whole principle of our British Constitution is that of the responsibility of Ministers to Parliament, and I think that the British Constitution being a gradual growth, and not a manufacture, is vastly superior to any Constitution even however carefully drawn up, as the American Constitution was. The very principle of the British Constitution is elasticity and development; whereas, the principle of the American Constitution is rigidity and finality. I think that in a young country like Australia any form of government should be as expansive as possible, so as to adapt itself to the constantly varying requirements of the future life of the colonies.”

Andrew Inglis Clark - delegate for Tasmania

“For my part I would prefer the lines of the American Union to those of the Dominion of Canada. In fact, I regard the Dominion of Canada as an instance of amalgamation rather than of federation, and I am convinced that the different Australian Colonies do not want absolute amalgamation. What they want is federation in the true sense of the word. The British North American Act, under which the Dominion of Canada was established, not only goes on the principle of defining the powers of the local Legislatures, as well as the powers of the Central Legislature, but also says that everything not included in the jurisdiction of the former is included in the jurisdiction of the latter, and it enables the Central Executive to veto the Acts of the local Legislatures. Well, I believe that, in the course of time, those who live to see the outcome will find the local Legislatures of the Dominion reduced to the level of the position of large municipalities, and that Canada will have ceased to be, strictly speaking, a federation at all. On the other hand, the American Constitution, as we all know, defines the powers of the Central Legislature, and reserves everything not included in them for the local Legislatures.

The other theme of this Conference (and the ones that were to follow) was the role of the electors, the citizens of the colonies, and how the colonial representatives at the Conference were there to represent the interests of both their legislatures as well as the electors, and that the electors must be given the opportunity to vote on who will be their representatives.

The Second Conference

The second National Australasian Convention was held in Sydney the following year, and the colonies sent many more delegates to the second one, although notably Western Australia was absent. The focus of the second convention moved to how the colonies would federate and members devoted themselves to finding a draft constitution on which they could agree, and one which they could take back to their legislatures for discussion and endorsement.

National Australasian Convention Sydney 1891 [B 480] • Photograph State Library of South Australia

Henry Parkes moved the following resolution:

That in order to establish and secure an enduring foundation for the structure of a federal government, the principles embodied in the resolutions following be agreed to:-

(1.) That the powers and privileges and territorial rights of the several existing colonies shall remain intact, except in respect to such surrenders as may be agreed upon as necessary and incidental to the power and authority of the National Federal Government.

(2.) That the trade and intercourse between the federated colonies, whether by means of land carriage or coastal navigation, shall be absolutely free.

(3.) That the power and authority to impose customs duties shall be exclusively lodged in the Federal Government and Parliament, subject to such disposal of the revenues thence derived as shall be agreed upon.

(4.) That the military and naval defence of Australia shall be intrusted to federal forces, under one command.

Subject to these and other necessary provisions, this Convention approves of the framing of a federal Constitution, which shall establish,

(1.) A parliament, to consist of a senate and a house of representatives, the former consisting of an equal number of members from each province, to be elected by a system which shall provide for the retirement of one-third of the members every years, so securing to the body itself a perpetual existence combined with definite responsibility to the electors, the latter to be elected by districts formed on a population basis, and to possess the sole power of originating and amending all bills appropriating revenue or imposing taxation.

(2.) A judiciary, consisting of a federal supreme court, which shall constitute a high court of appeal for Australia, under the direct authority of the Sovereign, whose decisions, as such, shall be final.

(3.) An executive, consisting of a governor-general and such persons as may from time to time be appointed as his advisers, such persons sitting in Parliament, and whose term of office shall depend upon their possessing the confidence of the house of representatives, expressed by the support of the majority.

Each element was discussed and debated for over a month.

The convention also debated the role of the Governor and whether each state would appoint their own, and what role Britain would have in decisions made by the new Australian parliament.

Amendments were made, and voted on. A draft version of the constitution was supported by a majority on April 9.

It was agreed that the electors of each colony had to vote on the constitution separately. Some noted that this may be a problem, and delay federation as each legislature could desire different changes. The issue of the tariffs and revenue raised by each colony continued to be a sticking point for many, with the fear that the larger colonies would continue to dominate the smaller ones. It was also agreed that support for federation had to be a majority of electors in each state, as well as a majority of states. This was decided as some colonies were much larger than others, and it was feared that their decision would be binding on the smaller states.

Why a Conference in Corowra?

The Corowa Conference was an unofficial gathering of supporters of federation in the town of Corowa on 31 July and 1 August 1893. The conference is famous for devising the mechanism whereby the federal movement could be voted on and agreed upon by all the colonies. The conference came out of the Federation Leagues that were established at the end of 1892 along the Murray River border between Victoria and NSW. Supporters of federation had decided that the draft constitution from the official convention in 1891 would probably not pass all the colonial Parliaments. The aim of the Leagues was to mobilise support for federation amongst the electors. William Lyne represented NSW, and the Premier and Opposition Leader from the Victorian Ministry were also in attendance.

The unofficial conference resolved on the second day that:

“in the opinion of this Conference, the best interests and the present and future prosperity of the Australian colonies will be promoted by their early union under the Crown.”

After further debate on the same day John Quick representing the Bendigo Australian Natives Association proposed what became known as the Corowa plan. The Native Association was first established in Victoria, made up of predominantly white, young males aged between 16-45 years. The term ‘native’ was meant to differentiate the members from those born in England or Europe.

The Corowra Plan

“That in the opinion of the Conference the Legislature of each Australian colony should pass an Act providing for the election of representatives to attend a statutory convention or congress to consider and adopt a bill to establish a federal Constitution for Australia and upon the adopting of such a bill or measure it be submitted by some process of referendum to the verdict of each colony”

Robert Garran and Alexander Peacock, two of the attendees at this Conference, wrote later that the novel element of the Corowa Conference plan was “the idea of mapping out the whole process in advance by Acts of Parliament – of making statutory provision for the last step before the first step was taken”. Equally important was the principle of popular involvement; this created both popular interest and confidence in the constitution-writing processes.

Quick’s procedure was adopted with slight modifications by four of the colonies at the Hobart Premier’s Conference in early 1895 and led to the Federal Conventions in 1897-98, and the eventual adoption of its draft constitution by referendum in 1899 and 1900.

Finishing Touches to Federation

When the Australasian Federal Convention met, in three sessions, in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne in 1897 and early 1898, the delegates modified the draft produced in 1891. Debates took place over a number of weeks, as each detail of the constitution and the makeup of the new legislature was finalised. How many senators in each state, and what will be the mechanism to increase that number. How will people vote in each state for the federal parliament and ensure it is fair and equal across every new state (once a colony). What would happen if one state allows women to vote in their elections, will that mean they can also vote in the federal elections. The much debated matter of taxes was included with Section 84 of the Constitution – The Commonwealth to have exclusive power to levy duties of customs and excise and offer bounties after a certain time, but then amended to add the specific time frame of within two years from the establishment of the Commonwealth.

Convention at NSW Parliament in 1897

Mr Edmund Barton rose to speak on 23 April 1897:

“I should like to make an explanation. It would be generally expected by members that votes of thanks would be passed to you, Mr. President, to the able Chairman of Committees, and to the Clerk of this Convention and his assistants, for their industrious and zealous work, but the reason why that proposal in not being made is that it is considered advisable that expressions of that kind should be deferred to the proper place at the next sitting of the Convention. I should like to express my acknowledgments to Sir George Turner and other members of the Convention who have spoken so much, and so much too kindly, of my work done as Leader of the Convention, and I can assure them their expressions were not heard by me unmoved. I have endeavored at all times to advance the cause which I think now every leading public man in Australasia has at heart, and I think the cause has been advanced. It is a satisfaction to me to recollect that, at a little gathering in the Town Hall, Melbourne, while on the way here, when the New South Wales delegates had the pleasure of being introduced to their colleagues from Victoria and Tasmania, I expressed the conviction that the work of this Convention could be got through within the period of a month, and it is exactly a month to-day since we opened our sittings. I should like to say this: Some of my colleagues in this Convention have expressed their thanks to the members of the committee associated with me in the preparation of the Bill, and I wish to express emphatically my thanks to them also. Their collaboration has been marked by an extreme feeling of patriotism, a deep sense of honor, and a thorough feeling of the importance of the work assigned to them, and their industry has been equal to the ability with which they have helped me in labors by no means slight. If there is any member of the Convention who thinks, in the warmth of debate, I may have discharged words in my expressions which seem to be too warm for the occasion, I can only say in the words of Shakespeare:

O Cassius, you are yoked with a lamb

That carries anger as the flint bears fire;

Who, much enforced, shows a hasty spark,

And straight is cold again.”

The convention finished a short time later that day with the draft constitution being sent to his Excellency the Governor, followed by three cheers for the Queen. In the final conventions the draft Commonwealth Constitution Bill was drawn up ready for each legislature to introduce.

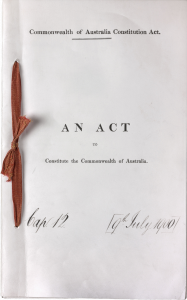

The Australian Constitution was contained in the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Bill, which was endorsed by the voters of each Australian colony at referendums in 1898, 1899 and 1900, passed by the British Parliament, and given Royal Assent on 9 July 1900.

Pictured is the Constitutional bill passed by British Parliament.

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office (Publisher), Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, 1900: Original Public Record Copy, 1900, courtesy of the Gifts Collection, Parliament House Art Collection, Department of Parliamentary Services, Canberra, A.C.T.